06172023

Father

He was born and raised in North Hampton, New Hampshire. His father, Samuel Parsons Garland Sr. took his own life at the age of eighty-six rather than be confined to a nursing home to die. His mother, Ida Tarr Garland, died a few years after the war. We never met. He rarely talked of her, though he was still engaged with the Tarr family, Rockport, MA, into the seventies.

He joined the Navy in 1941, after Pearl Harbor. He became part of the SeaBees, the construction battalion, and spent the war in the South Pacific. I had banners in my room when I was growing up, mementos of the islands he had been to. Palau. New Caledonia. Hebrides, and on.

He married my mother after the war and they set about building a big family, eight kids in all. He worked as a bartender for a while. He was a bartender when I was born. Story is, he worked the night I was born, and everybody kept buying him drinks. He smashed into a parked car on his way home. Been in trouble if my uncle wasn’t a town cop.

He worked as a lineman, running electrical wires in New England. He’d leave the house early in the morning, five or so. I vowed I’d never work a job where I’d have to leave so early. I had a job when I had to leave that early.

He’d get home from work at five. My mother would have dinner ready for him when he arrived. After he’d fall into his chair and watch the news. Cronkite or Huntley / Brinkley, then whatever fare was offered by one of the three networks. He liked war shows. Combat. He’d usually fall asleep in the chair by eight-thirty. He and my mother would hold hands while they watched.

He smoked Camels. Couple of packs a day. I went to Binette’s Market umpteen times, a hot quarter in my hand. Pack of Camels, please. Smoke ‘em if you’ve got ‘em. If there wasn’t an ashtray and he was indoors, he’d flick the dead ash into the cuff of his pants as he sat and talked.

He had a series of stodgy family cars. ’52 Olds. Galaxie 500. Family sedans. One time in the mid-sixties he arrived home in a sporty little Pontiac Tempest. Light yellow. Bucket seats. My mother made him get rid of it. It was one of his bids for independence, I think. A car that wouldn’t fit the whole growing brood.

He loved the ocean. I was about eight when he got his first boat, a small aluminum skiff with a low-horse Evinrude. He was so pleased. Immediately took us younger kids and my mother and launched the boat into the Hampton River. Overloaded a little, water up to the gunwales. Mom started to panic when he turned the boat toward open sea. Sam, you turn this boat around RIGHT NOW!

He graduated to more seaworthy boats as time went by. I became his first mate on a multitude of deep-sea fishing expeditions. He knew fishing spots. He trusted the sea, and I trusted him. He never wanted to return to dock. We were caught in fog. We were caught in thunderstorms. A navy guy.

I never saw him cook, except barbecue. He taught me how to barbecue. Dogs and burgers. Relish in the middle and mustard on top.

He and mom had date nights most every Friday. They’d either go out for Chinese or fried clams. In the morning I’d find either chewy sesame candy or leftover fried onion rings, Delicious.

We never went out to a restaurant as a family. Too many of us. Too expensive. I must have been twelve or thirteen the first time we stopped at a Chinese restaurant in Wenham, MA. China Dragon. Set off a lifelong love affair with Chinese cuisine, though that afternoon I’m sure it was the basics: appetizers, Egg Foo Yung, chow Mein. Chewy sesame candies.

He would take the family on Sunday afternoon drives, at mom’s insistence. Sometimes to Kingston, where he’d found an ice cream stand on some rural back road that sold banana boats, six scoops, all the toppings, served in a blue plastic boat, for a quarter.

He read. Zane Grey. Earl Stanley Gardner. The Boston Herald, every day. He loved jazz. Kept trying to get me to appreciate Errol Garner. I was young, unconvinced. Only later did I grow to appreciate Garner’s genius. On the day I learned of dad’s death, I listened to Garner’s “Autumn Leaves” for a long time.

Another of his favorites was Glenn Miller. I’ve always liked Miller’s music too. And Ella Fitzgerald. Mom would sing scat while she cooked. He took us to the movies sometimes. Drive-ins, mostly. Double features. Once we sat through the first feature, some horror movie about a test pilot who takes his jet too high and on the return he’s somehow turned into this murderous mutant monster. I loved it. When the second feature started, Beach Blanket Bingo, we left in a hurry. He took me to the Ioka to see The Longest Day.

There was a blizzard in New England in ’69. Snowed four days. Still remember seeing pictures in the Ipswich Chronicle, snow drifts as high as the top of utility poles. I was helping him lay a new carpet in the family room, Sunday afternoon, when the first flakes fell. The phone rang and the snow started at the same time. He was gone within an hour. Didn’t see him for a week. My job was to split wood and keep the fireplace lit. No power. When the storm broke, I shoveled the car out as best I could and tried to move it, but it was hopelessly stuck. I flattened a rear tire in my attempts. I’m sure I made the situation much worse. He never said anything about it. Just thanked me. He said it was the biggest paycheck he’d ever received.

He was a social drinker. Rarely saw him with a beer. Highballs. Coffee was his quaff of choice, any time of day. Percolated. Regular. He was a congenial guy, easy with people, had friends. Had a way of teasing that was disarming, made him likeable. He could say things to people that would get someone else smacked, but he could pull it off.

He once had to pull a friend and colleague off a wire after watching him die from electrocution. He was a lineman in the days before bucket trucks, when workers had to strap on spikes and belts to climb utility poles. He was strong as an ox in his youth. After mom died in ’76, he moved to a smaller house, an old New Englander, two story, three bed. He carried on, with three daughters left at home. I was working with a publicist for the Boston Bruins, who would occasionally provide tickets for the games. He and I would go to the Garden down ninety-five in his huge Catalina.

He eventually remarried. Bought a light metallic green ’68 Camaro. First time I drove it I got my first speeding ticket, test drive with two little sisters. Thirty-seven in a twenty-five zone. I stood as his best man. Small ceremony. They sold everything and moved to the Keys. Bought a houseboat. He ran fishing charters. We lost touch. There was a family-wide resentment that he’d sold our heritage without letting us know, before we could perhaps take something to remember our mother by. I rarely spoke to him in the last years of his life.

There was also the feeling that he neglected the proper supervision of his youngest daughter, who went wild in Florida.

He rarely spoke of the war.

He liked to be busy. He liked to work. He was always remodeling this or that. New kitchen. Screen porch converted to a spare room. The houses we lived in were always too small for the family. When we moved from Exeter to Ipswich, sister Ann was left behind to live with mom’s parents. Don’t know if she ever forgave him for that. When he moved from Ipswich to Portsmouth, I was going from my sophomore to junior year. I don’t know if I ever forgave him for that. Though I did meet my future wife at Portsmouth High. I bear no grudge. It worked out. I saw him only once after his Florida move. He’d visited New Hampshire. I was living in Maine, raising my own family. Jason was two. Jen was newborn. Jason and I drove to Ed’s house in Manchester. I don’t remember any real conversation. It was a chance for him to meet his grandson. It was a sunny day. It was a three-and-a-half-hour drive, one way. It was a short visit

He never talked politics. I don’t know if he ever voted. Never went to church. Called himself a “home Baptist.” His mother played organ at the North Hampton Baptist Church. He told us of one Halloween night he and his friends took all the pews from the church and arranged them on the roof. Pranks. A slant of humor passed onto his children.

He would take mom to see her parents, Water Street in Exeter, every week. Bill and Theresa Howard. Bill and Theresa would come over many Saturday nights for dinner and an evening of cards. Gin Rummy. Bill Howard was a Gin Rummy shark. Raucous, the laughter around that old maple table.

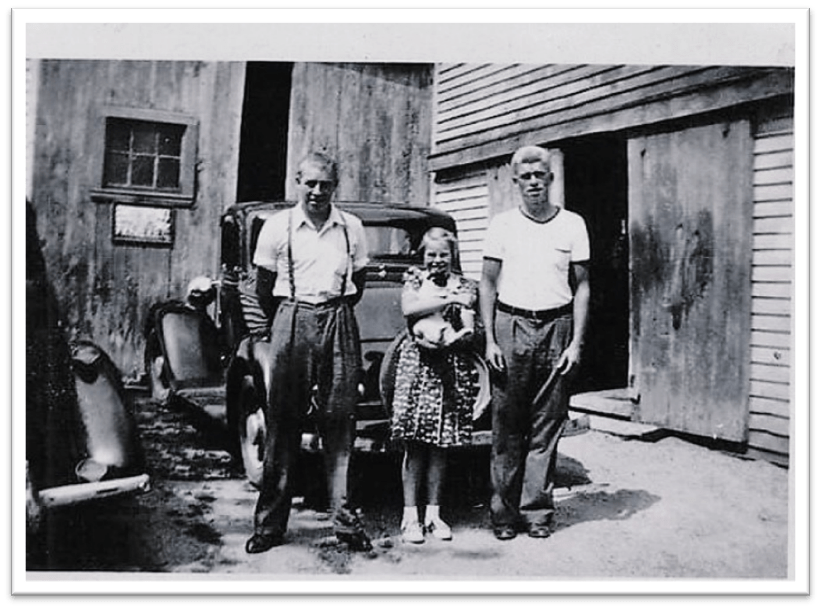

He was blond in his youth. At some point he’d broken his nose, or someone else had, and it had a slight crook in it. He had a toothy, sideways kind of smile, genuine.

Oddly, I was with my brothers when we learned of his death. Cloudy fall day. We were picking apples in an orchard behind Bill’s house. Cortlands and Macs. Ruth Ann came from the house, shouted that Sheila was on the phone. Bill came back out and told us Dad had died a couple of weeks before. Heart. No funeral. No one went to Florida. I never learned what arrangements had been made. Where he ended up. Missed him for a long time. Taught me a lot about being a man, about life.

Happy Father’s Day. Dad.

Sam (left), Phoebe, Bob Garland 1939